Appendix G: Understanding piezoelectric parameters

Contents

- Basic piezoelectric relations

- Young's moduli

- Piezoelectric coupling coefficient κ — physical interpretation

- Power — further considerations

- Figures

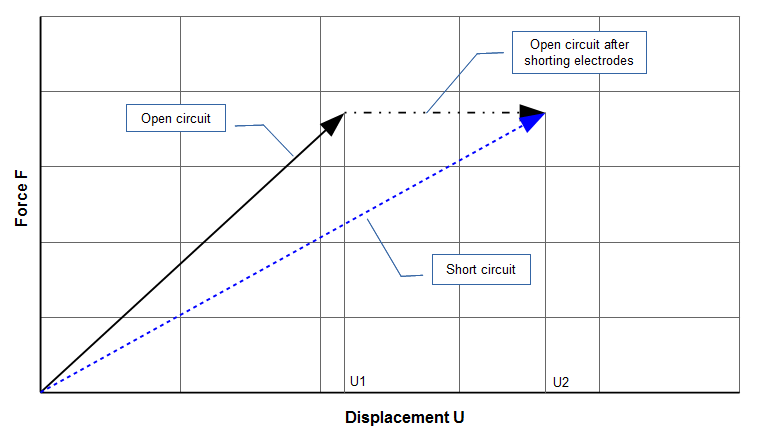

- Figure 1. Piezoelectric ceramic — force versus displacement

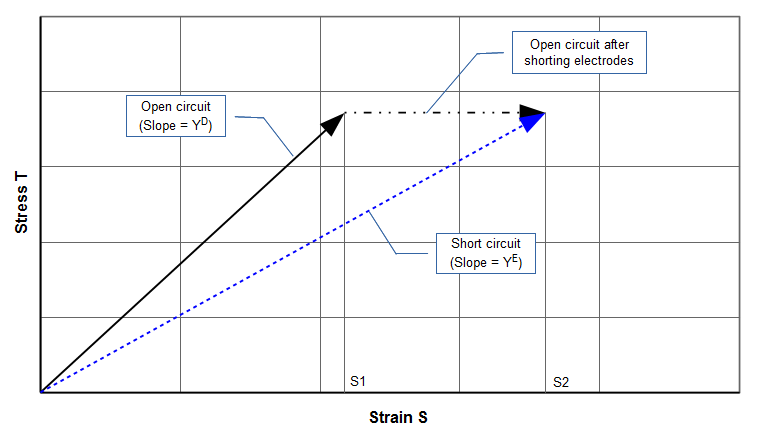

- Figure 2. Piezoelectric ceramic — stress versus strain

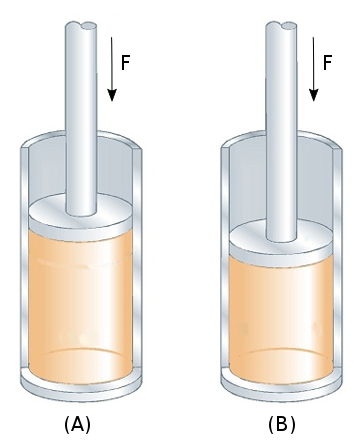

- Figure 3. Compressed gas — (A) Adiabatic, (B) Isothermal

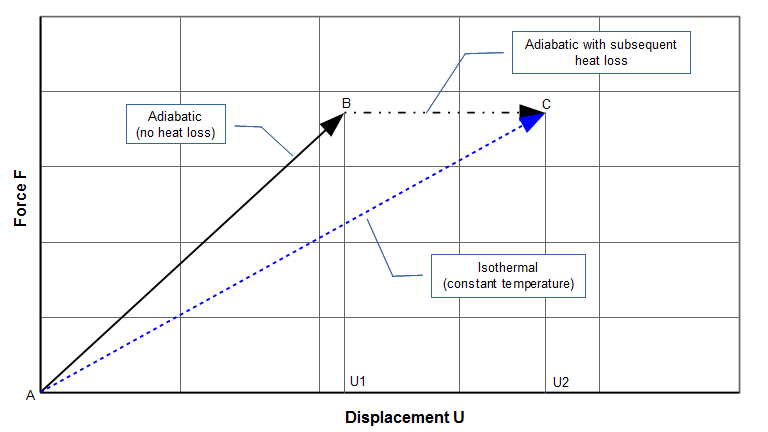

- Figure 4. Compressed gas — adiabatic versus isothermal

- Figure 5. 20 kHz industrial transducer with six piezoelectric ceramics (33 mode)

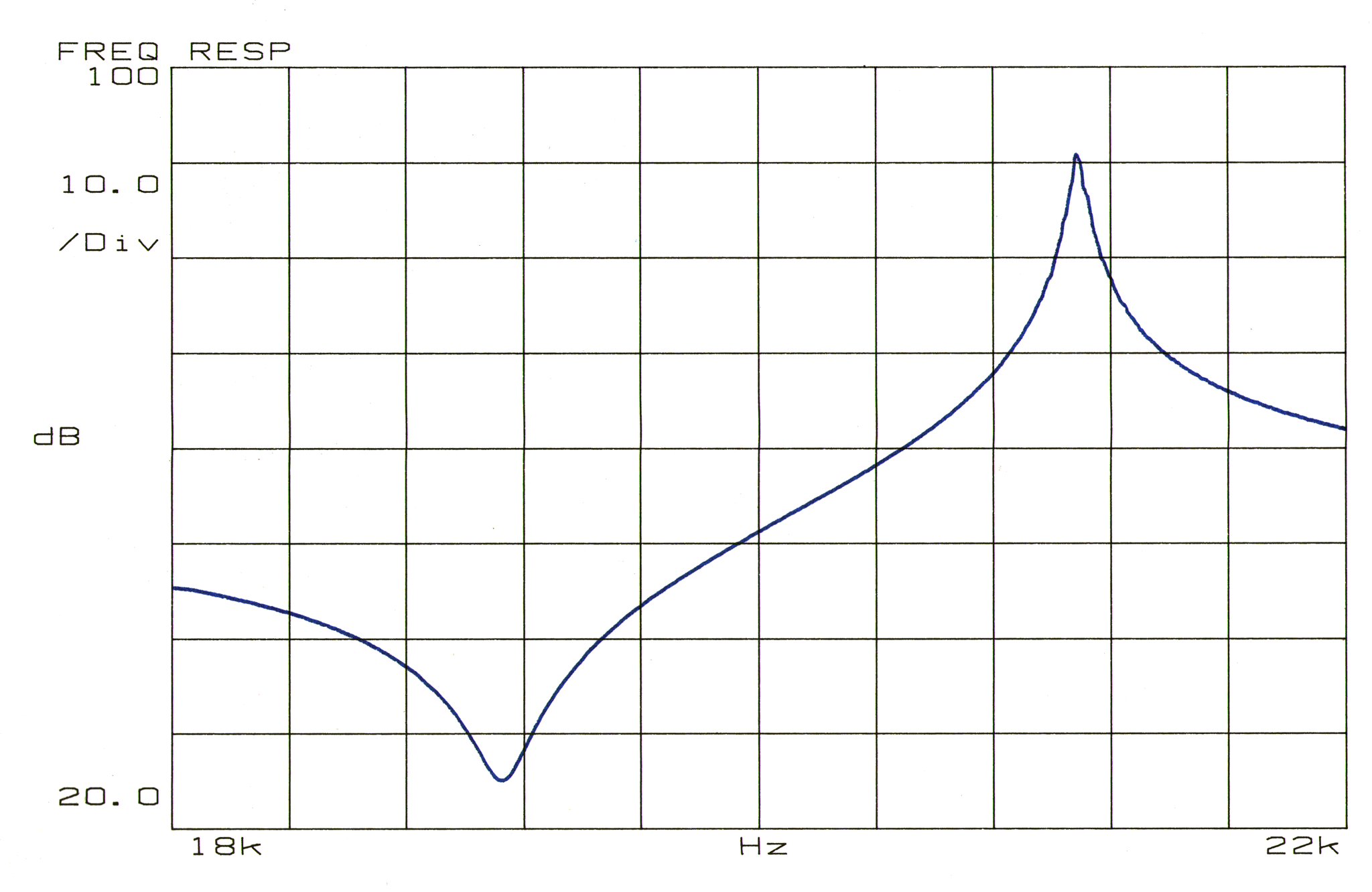

- Figure 6. Frequency response impedance plot for 20 kHz transducer

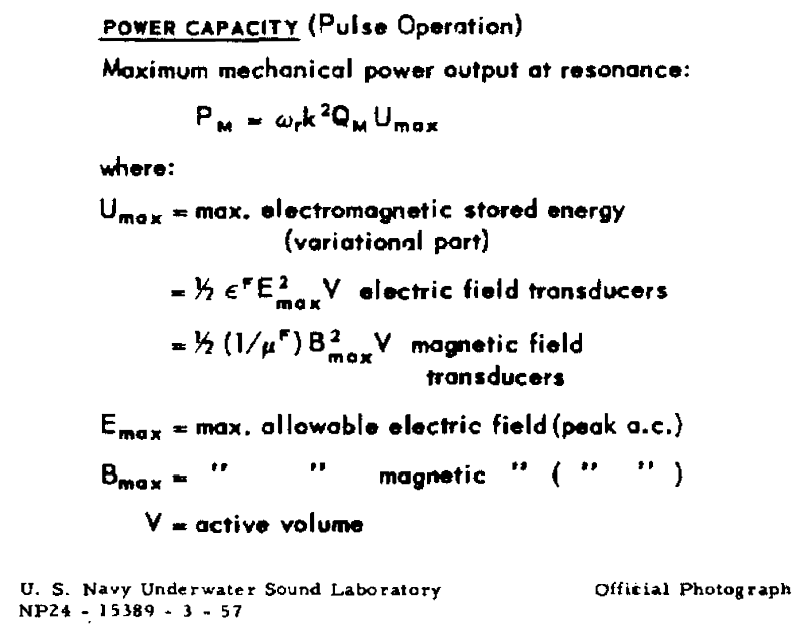

- Figure 7. Maximum mechanical power output at resonance

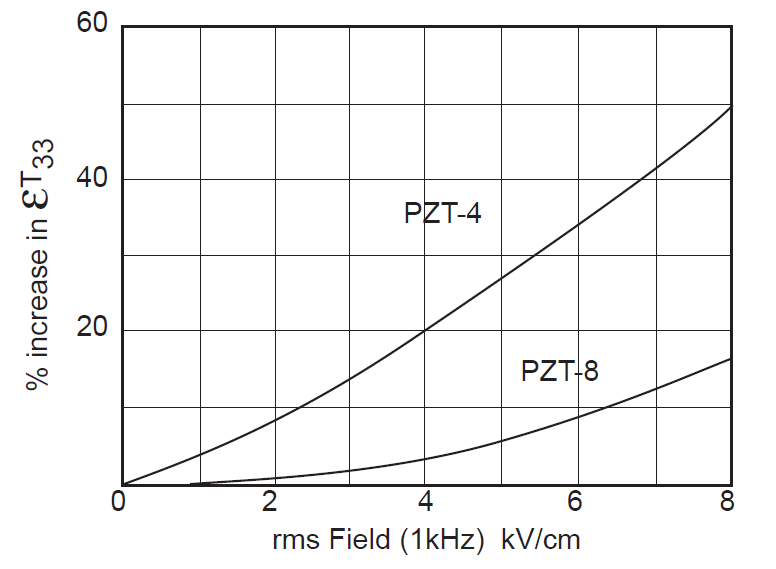

- Figure 8. Effect of electric field strength on piezoceramic permittivity

- Tables

This appendix shows the relations between various piezoelectric parameters and constants and how these are affected by the mechanical and electrical boundary conditions.

Notes —

- The following discussion uses symbols that are commonly found in the piezoelectric literature. These differ from symbols that are traditionally used for elasticity.

- The equations below typically use a single symbol to desigate a characteristic of the ceramic. Actually, however, this symbol often represents a matrix of property constants. For example, the elastic compliance is designated by \( s \) which is actually the matrix —

- The equations below assume linear behavior which will be true at low drive levels. However, ceramic behavior becomes nonlinear at high drive levels; none-the-less, the equations give guidance to the relationships among the parameters.

|

||||||||||||

|

\begin{align} \label{eq:10001b} \nonumber s = \left[ \begin{matrix} s_ {11} &s_ {12} &s_ {13} &0 &0 &0 \\ s_ {21} &s_ {22} &s_ {23} &0 &0 &0 \\ s_ {31} &s_ {32} &s_ {33} &0 &0 &0 \\ 0 &0 &0 &s_ {44} &0 &0 \\ 0 &0 &0 &0 &s_ {55} &0 \\ 0 &0 &0 &0 &0 &s_ {66} \\ \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}

To avoid some complexity associated with manipulating such matrices and without undue loss of generality, the following will assume that all stresses are uniaxial (i.e., no transverse or shear stresses) and that the piezoelectric materials are isotropic. (In fact, piezo ceramics can be quite anisotropic. For example, Piezo Technologies (p. 6) states that "the speed of sound in the radial direction is often 20% to 30% higher than the speed in the axial direction.")

Basic piezoelectric relations

All solids deform when subjected to an applied force. The relation between strain \( S \) and stress \( T \) is —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10001a} S &= s \,T \end{align}

where \( s \) (lower case) is the material's compliance (the inverse of Young's modulus). This equation assumes a linear relation between \( S \) and \( T \), at least over the range of interest. This linearity will be assumed for all subsequent equations.

If a material is dielectric (like a capacitor) then the relation between the areal charge density \( D \) and the applied electric field \( E \) is —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10002a} D &= \varepsilon \,E \end{align}

where \( \varepsilon \) is the permittivity of the material. The above parameters are summarized in table G2.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Note that equations \eqref{eq:10001a} and \eqref{eq:10002a} do not involve any piezoelectric effects (i.e., there is no interaction between the mechanical effects of equation \eqref{eq:10001a} and the electrical effects of equation \eqref{eq:10002a}). However, if a material is piezoelectric then an additional term must be added to each equation to account for the piezoelectric effect. For the inverse (converse) piezoelectric effect where an electric field causes a strain in the material, equation \eqref{eq:10001a} must be modified by adding the term \( d^T E \).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10003a} S &= s^E \,T + d^T \,E \end{align}

where \( d \) is the piezoelectric charge constant (see table G4) (The superscripts, which denote constraints, are explained below). With the addition of the charge constant \( d^T \), the strain \( S \) can be nonzero (due to the electric field \( E \)) even when the stress \( T \) is zero.

An alternate but complementary piezoelectric effect is where an external stress causes a charge to build up in the piezoelectric material. (This is the direct piezoelectric effect and was first investigated by the Curies.) To account for this effect, equation \eqref{eq:10002a} must be modified by adding the term \( d^E T \).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10004a} D &= \varepsilon^T \,E + d^E \,T \end{align}

where \( d \) is, again, the piezoelectric charge constant. With the addition of the charge constant \( d^E \), the charge \( D \) can be nonzero (due to the stress \( T \)) even when the electric field \( E \) is zero.

Note that if \( d \) = 0 (i.e., the material is not piezoelectric) then equations equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} just reduce to equations \eqref{eq:10001a} and \eqref{eq:10002a}, respectively. Hence, the piezoelectric characteristics of the material are defined by the charge constant terms \( d^T \) and \( d^E \).

Equation notes —

- Equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} are actually not complete since other parameters may affect the performance. For example, the strain \( S \) will change if the temperature of the material changes. Therefore, a term like \( \alpha H \) should be added, where \( \alpha \) is the coefficient of thermal expansion and \( H \) is the temperature rise.

\begin{align} \label{eq:10099a} S &= s^E \, T + d^T \, E + α \, H \end{align}

Thus, the strain is affected by temperature in a similar manner to the electric field. If the material were magnetostrictive then the magnetostrictive effect should also be considered. The equations given here implicitly assume that these effects are not present (for example, that the material is maintained at a constant temperature) or that these effects can be ignored. - Although equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} are often shown in the current form, the variables can easily be rearranged to give alternate equations.

Superscripts (constraint boundary conditions)

A superscript on one of the constants indicates that the superscript parameter is being held constant (constrained). For example, consider the compliance parameter \( s \) with the superscript \( E \) (i.e., \( s^E \)) in equation \eqref{eq:10003a}. \( s^E \) indicates that the electric field strength \( E \) is held constant when the elastic compliance \( s \) is determined (e.g., when the material is stress-strain tensile tested). If \( E \) were not held constant then part of the strain \( S \) would result from the piezoelectric effect of \( d^T E \) and the measured value of \( S \) would not be correct. (In a similar manner, the temperature is kept constant during a stress-strain tensile test so that the strain is only affected by the stress, not by any thermal expansion.)

Similarly, the dielectric constant \( \varepsilon \) in equation \eqref{eq:10004a} can only be properly evaluated when the stress \( T \) is held constant (i.e., \( \varepsilon^T \)). Otherwise, part of the dielectric displacement \( D \) would be due to the stress \( T \) rather than the electric field \( E \) and the measured value of \( \varepsilon \) would not be correct.

Common constraints are summarized in table G3.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Table G3 notes —

- A state of constant strain cannot be practically achieved by physically restraining the piezoelectric ceramic. However, it can be achieved by exciting at a very high frequency where the inertial effects become so large that the ceramic effectively cannot vibrate (i.e., there are no strains). (See Cady (1), pp. 328, 572.) The same situation occurs when a single degree-of-freedom spring-mass system is excited at a frequency that is very high compared to its resonant frequency — the mass will not move from its rest position.

- The condition of constant electric field (constant \( E \)) is most easily achieved by short circuiting the ceramic's electroded faces so that no electric field can exist (i.e., \( E=0 \)). Hence, a parameter that is evaluated at a constant electric field \( E \) may be referred to as a short circuit parameter.

- The condition of constant dielectric displacement (constant \( D \)) is most easily achieved by open circuiting the ceramic's electroded faces so that no current can flow (i.e., \( D=0 \)). Hence, a parameter that is evaluated at a constant dielectric displacement \( D \) may be referred to as an open circuit parameter.

Based on the above constraints, table G4 shows several piezoceramic parameters. The relationship of these parameters will be discussed later.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Significance of the charge constant \( d \)

When the transducer is used as a transmitter (per the applications of this site), the charge constant \( d^T \) is particularly important because it determines how much the piezoelectric material expands or contracts when an electric field is applied (termed the reverse piezoelectric effect). In this case, a large charge constant is desirable so that a high amplitude (displacement) is achieved for a given electric field.

(When the transducer is used as a receiver, \( d^E \) determines how much charge is generated when the piezoelectric material is subjected to a stress (termed the direct piezoelectric effect). However, the direct effect is relatively unimportant for power transducers except where a separate piezoceramic is used in the transducer as electrical feedback to monitor the transducer's amplitude.)

Although \( d^T \) and \( d^E \) have different units, their numerical values in the S.I. system are identical (see Berlincourt (3), equation 24a, p. 188). Hence, equations \eqref{eq:10003a} and \eqref{eq:10004a} are generally written without the \( T \) and \( E \) superscripts on \( d \).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10007a} S &= s^E \,T + d \,E \end{align}

\begin{align} \label{eq:10008a} D &= \varepsilon^T \,E + d \,T \end{align}

Alternate equation formulations

As mentioned above, these equations can be rearranged to give other constants. For example, solving equation \eqref{eq:10008a} for \( E \) and substituting into equation \eqref{eq:10007a} gives —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10009a} S &=s^{E} \,T + \frac{d}{\varepsilon^{T}}D - \frac{d^{2}}{\varepsilon^{T}} T \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &= s^{E} \,T + \frac{d}{\varepsilon^{T}}D - \frac{s^{E}}{s^{E}} \frac{d^{2}}{\varepsilon^{T}} T \nonumber \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &= s^{E}\left[1 - \frac{d^{2}}{s^{E} \varepsilon^{T}}\right] T + \frac{d}{\varepsilon^{T}} D \nonumber \end{align}

Equation \eqref{eq:10009a} can be simplified by consolidating the constant factors into two new constants — i.e.,

\begin{align} \label{eq:10010a} \kappa &=\frac{d}{\left(s^{E} \varepsilon^{T}\right)^{1/2} } \end{align}

\begin{align} \label{eq:10011a} g^{T} =\frac{d}{\varepsilon ^{T}} \end{align}

where —

|

|||||||||

|

(See Piezoelectric coupling coefficient for an alternate derivation of \( \kappa \) and a description of its significance.)

Then \eqref{eq:10009a} becomes —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10012a} S=s^{E} (1 - \kappa^{2}) \,T + g^{T} D \end{align}

If \( D \) is held constant (e.g., by disconnecting the electrodes (open circuit) so that no charge can flow — i.e., \( D \) = 0) then equation \eqref{eq:10012a} becomes —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10013a} S=\left[s^{E} (1 - \kappa^{2})\right] \,T \end{align}

Equation \eqref{eq:10013a} defines the relation between the strain and stress when the ceramic's electrodes are open circuit (i.e., \( D \) = constant). Hence, the factor \( s^E (1 - \kappa^2) \) is the compliance at open circuit, denoted as \( s^D \) —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10014a} s^{D} = s^E(1 - \kappa^{2}) \end{align}

Then substituting equation \eqref{eq:10014a} into equation \eqref{eq:10012a} gives —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10015a} S=s^{D} \,T + g^{T} D \end{align}

(See Berlincourt (3), equation 21a, p. 188.)

Compared to equation \eqref{eq:10003a}, the strain \( S \) in equation \eqref{eq:10015a} is now expressed in terms of stress \( T \) and dielectric displacement \( D \) with constants \( s^D \) and \( g^T \), respectively. The choice between equation \eqref{eq:10003a} and equation \eqref{eq:10015a} is completely arbitrary (although equation \eqref{eq:10003a} is more common).

Young's moduli

Equation \eqref{eq:10014a} shows that the piezoceramic can have two distinct compliances, \( s^E \) and \( s^D \). This results from the coupling of the mechanical and electrical characteristics of the piezoceramic.

Equation \eqref{eq:10014a} is expressed in terms of compliances. However, since Young's modulus \( Y \) is just the inverse of the compliance \( s \) (i.e., \( Y=s^{-1} \) or \( Y=1/s \) for an isotropic material), equation \eqref{eq:10014a} can be written as —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10016b} \frac{1}{Y^D} = \frac{1}{Y^E}(1 - \kappa^{2}) \end{align}

or

\begin{align} \label{eq:10016a} Y^D=\frac{Y^E}{1 - \kappa^{2}} \end{align}

where —

| \( Y^D \) | = Young's modulus at open circuit |

| \( Y^E \) | = Young's modulus at short circuit |

(As previously noted, Young's modulus is usually represented by \( E \). However, since \( E \) is used here for the electric field strength, Young's modulus is represented by \( Y \) instead.)

Thus, the piezoceramic has two different Young's moduli, depending on the electrical boundary conditions (short circuit or open circuit). Since \( \kappa \) is always less than 1.0, the open circuit modulus \( Y^D \) is always greather than the short circuit modulus \( Y^E \).

Physical explanation

This section presents a physical explanation for the two Young's moduli. (Note — The following graphs are only for illustration. The X-axis and Y-axis grids have no particular scale and cannot be directly compared between graphs.)

Consider a piezoceramic that is compressed by gradually applying a force up to \( F \) (see figure G1). If the piezoceramic's electrodes are open circuit (no conduction path) then part of the energy of compression goes toward toward establishing an electric field (i.e., a charge separation due to the piezoceramic's capacitance); the remaining (depleted) energy goes toward deforming the piezoceramic. Thus, the force \( F \) produces a displacement \( U_1 \). This is the solid line.

Now if the compressed piezoceramic is short circuited then the electric field disappears. The associated energy of the electric field also disappears but, because this is a conservative system, that lost electrical energy must be converted into another form of energy. The converted energy results in additional strain of the piezoceramic so the displacement increases from \( U_1 \) to \( U_2\) (the dash-dot line). Thus, the piezoceramic compresses more at short circuit than at open circuit. (If the piezoceramic had originally been short circuited, then the force \( F \) would have directly deformed it to \( U_2\) (the dashed line) without going through the intermediate open circuit step.)

|

|

|

Figure G1 can be converted to the usual stress-strain diagram of figure G2. Young's modulus \( Y \) is the slope of the appropriate stress-strain curve. Figure G2 shows that the short circuit (dashed) line has a lower slope than the open circuit (solid) line (i.e., for a given stress, the strain at short circuit \( S_2 \) is greater than the strain \( S_1 \) at open circuit). Thus, Young's modulus at short circuit (\( Y^E \)) must be lower than the Young's modulus at open circuit (\( Y^D \)).

|

|

|

Compressed gas analogy

Figure G3 shows a cylinder where a gas is compressed by gradually applying a force up to \( F \). In the left image the cylinder is insulated so that no heat can escape. This is the adiabatic condition (the solid line AB in figure G4). During the compression process the temperature (thermal energy) of the gas has increased compared to its uncompressed state. The increase in thermal energy limits the displacement to \( U_1 \).

Now suppose that the excess thermal energy is allowed to drain off through the walls of the cylinder so that the temperature returns to its original state. Since the piston force is unchanged, the loss of thermal energy means that the gas can no longer support the same piston force at its previous position; thus the piston drops to a new equilibrium position \( U_2 \) (the right cylinder image). This is the dash-dot line BC in figure G4.

The same end-state C would have been achieved if the cylinder had been uninsulated during the entire loading process. Then no thermal energy would have accumulated and the loading would have progressed smoothly from A to C (the dashed line). This is the isothermal (constant temperature) condition.

Thus the gas compresses more under isothermal conditions (line AC) than under adiabatic conditions (line AB) so the isothermal bulk modulus (\( B_T \)) must be lower than the adiabatic bulk modulus (\( B_S \)). This is similar to the piezoelectric modulus (\( Y \)) where the short circuit modulus (\( Y^E \)) is lower than the open circuit modulus (\( Y^D \)).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Short circuit and open circuit resonances

Since the piezoceramic has two Young's moduli, it must also have two associated resonances. The resonance that is associated with \( Y^E \) is called the short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \). The resonance that is associated with \( Y^D \) is called the open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \). (The short circuit resonance is also called series resonance; the open circuit resonance is also called parallel resonance. The reasons will be discussed elsewhere. zzz explain distinction) The relation between these resonances is shown below.

Since the resonant frequencies are proportional to the square root of Young's modulus (i.e., \( f\propto \sqrt{Y} \)), equation \eqref{eq:10016a} can be written in terms of short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \) and open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \) as:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10018a} {f_{oc}}^2={f_{sc}}^2 \left(\frac{1}{1 - \kappa^{2}} \right) \end{align}

or

\begin{align} \label{eq:10019a} {f_{oc}}={f_{sc}} \, \sqrt{\frac{1}{1 - \kappa^{2}} } \end{align}

where —

| \( f_{sc} \) | = short circuit resonance |

| \( f_{oc} \) | = open circuit resonance |

Note that \( \kappa \) has a value between 0 and 1 (see below) so the quantity under the radical of equation \eqref{eq:10019a} is always \( \geq 1 \). This means that the open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \) will always be greater than the short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \); the relative difference will depend on the coupling coefficient \( \kappa \).

Figure G6 shows a frequency response impedance plot for the 20 kHz transducer (Branson 502) of figure G5. The impedance dip corresponds to the short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \). The impedance peak corresponds to the open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \). (This transducer is designed to operate at open circuit (parallel) resonance. The open circuit resonance frequency (~20.8 kHz) is somewhat higher than the 20 kHz design frequency because the transducer does not have a front stud. Adding the front stud would drop the frequency into the desired operating range.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Piezoelectric coupling coefficient κ — physical interpretation

The energy that is stored in a piezoelectric material can take three forms — elastic (strain) energy, capacitive electrical energy, and coupled electromechanical energy. To show this, equations \eqref{eq:10007a} and \eqref{eq:10008a} can be expressed in terms of energies by multiplying \eqref{eq:10007a} through by \( T \)/2 and \eqref{eq:10008a} by \( E \)/2:

\begin{align} \label{eq:10020a} \small\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \,S \,T &= \small\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \,s^E \,T^2 + \small\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \,d \,E \,T \end{align}

\begin{align} \label{eq:10021a} \small\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \,D \,E &= \small\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \,\varepsilon^T \,E^2 + \small\frac{1}{2}\normalsize \,d \,E \,T \end{align}

Note that the energies in these equtions are actually energy densities (i.e., energy per unit volume).

In equation \eqref{eq:10020a}, \( \frac{1}{2} S \, T \) is the total stored mechanical energy. This is composed of the strain energy \( \widehat{W}_1 \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} s^E \, T^2\)) and the coupled piezoelectric energy \( \widehat{W}_{12} \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} d \,E \, T \)).

In equation \eqref{eq:10021a}, \( \frac{1}{2} D \, E \) is the total stored electrical energy. This is composed of the stored capacitive energy \( \widehat{W}_2 \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} \varepsilon^T \, E^2\)) and, again, the coupled piezoelectric energy \( \widehat{W}_{12} \) (\( = \frac{1}{2} d \,E \, T \)).

The coupling coefficient \( \kappa \) can be expressed in terms of the above energies as (Waanders (1), equation A8, p. 84 or Berlincourt (3), equation 30, p. 190) —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10022a} \kappa &= \frac{\widehat{W}_{12}}{(\widehat{W}_1 \,\widehat{W}_2)^{1/2}} \end{align}

where —

| \( \kappa \) | = Piezoelectric coupling coefficient |

| \( \widehat{W}_1 \) | = Total stored mechanical energy |

| \( \widehat{W}_2 \) | = Total stored electrical energy |

| \( \widehat{W}_{12} \) | = Coupled piezoelectric energy |

Thus, the coupling coefficient is the ratio of the coupled piezoelectric energy to the geometric mean of the stored mechanical energy and stored electrical energy.

Substituting the specific energy terms from equations \eqref{eq:10020a} and \eqref{eq:10021a} into \eqref{eq:10022a} gives —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10023a} \kappa &= \frac{\frac{1}{2} \,d \,E \,T}{\left[(\frac{1}{2} \,s^E \,T^2) \,(\frac{1}{2} \,\varepsilon^T \,E^2)\right] ^{1/2}} \\[0.7em]%complex_eqn_interline_spacing &=\frac{d}{\left(s^{E} \, \varepsilon^{T}\right)^{1/2} } \nonumber \end{align}

Note that equation \eqref{eq:10023a}, which has been derived from energy considerations, is the same as equation \eqref{eq:10010a}.

For a single piezoceramic, \( \kappa \) depends on the element's shape, mode of excitation (e.g., longitudinal, radial, thickness) and boundary conditions. Table G6 shows the most common conditions under which \( \kappa \) is evaluated for single piezoceramics. The subscripts on \( \kappa \) denote the prescribed conditions (see the notation here).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The above defined coupling coefficients can be used when specifying or evaluating the performance of individual piezoceramics. They can also be used as reference values for comparison to completely assembled transducers.

Equation \eqref{eq:10019a}, by which the coupling coefficient can be determined, can be applied to a single piezoceramic of arbitrary condition (arbitrary shape, constraints, etc.) or to an entire transducer. For the later case, the terminology then becomes the effective piezoelectric coupling coefficient \( \kappa_{eff} \). (Alternately, \( \kappa_{33} \), \( \kappa_{31} \), \( \kappa_{t} \), \( \kappa_{p} \), and \( \kappa_{u} \) can be considered special cases of the more general \( \kappa_{eff} \).) Woollett (1) (p. 24) notes, "However, the transducer coupling coefficient is usually less than the coefficient of the material used in its construction, and is designated as the effective \( \kappa \) to distinguish it from the \( \kappa \) of the material." The effective value of \( \kappa \) (i.e., \( \kappa_{eff} \)) will depend on the particular transducer's design (e.g., the effect of the stack bolt, the placement and length of the ceramics, etc.).

Note that most power transducers vibrate in the 33 mode. However, \( \kappa_{33} \) is not appropriate for this mode since it applies to a long thin bar or rod. Instead, \( \kappa_{t} \) should be used since it is for a thin disc.

From equation \eqref{eq:10018a} or \eqref{eq:10019a}, any of the coupling coefficients can be calculated from their associated open circuit resonance \( f_{oc} \) and short circuit resonance \( f_{sc} \) frequencies. (Also see Waanders (1), equation A19a, p. 85).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10024a} \kappa _{eff} &= \left[1 - \left( \frac{ f_{sc} } { f_{oc} } \right)^2 \right]^{1/2} \end{align}

The required frequencies may be known from analytical analysis or from measurements of actual piezoceramics or assembled transducers. For example, for the transducer of figure G5, the open circuit and short circuit frequencies (from figure G6) are 20.8 kHz and 18.8 kHz, respectively. Hence, \( \kappa_{eff} \) for this transducer is 0.43.

Significance of κ

Berlincourt (3), (p. 189) asserts, "The most important properties of piezoelectric materials are their piezoelectric coupling factors."

The significance of \( \kappa \) can be determined from equation \eqref{eq:10022a}. The numerator represents the converted energy while the denominator represents the total input energy (Waanders (1), p. 12).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10025a} \kappa &= {\left[\frac{\text{Energy converted}}{\text{Energy input}} \right]}^{1/2}_{\text {Low frequency}} \end{align}

Since the "Energy converted" must always be less than the "Energy input", \( \kappa \) must always be less than 1.0.

In order to achieve the maximum piezoelectric effect, it is desireable to convert as much input energy into piezoelectric energy as possible. Therefore, \( \kappa \) for the individual ceramics and \( \kappa_{eff} \) for an assembled transducer should be as large as possible. Maximizing \( \kappa \) will also maximize both \( d \) and power.

Maximized \( d \)

See equation \eqref{eq:10023a}. This will maximize the output amplitude.

Maximized power

Berlincourt (3) (p. 250, equation 147) gives the following equation for the theoretical power that can be developed by an ultrasonic transducer.

\begin{align} \label{eq:10026a} p &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, {E_3}^2 \, \kappa^2 \, \varepsilon_{33}^T \, Q_M \end{align}

where —

| \( p \) | = Acoustic power density (power per unit volume of piezoceramic) [W/m3] |

| \( f_{sc} \) | = Short circuit (series) resonance frequency [Hz] |

| \( E_3 \) | = Electric field strength [VRMS/m] |

| \( \kappa \) | = Electromechanical coupling factor [no units] |

| \( \varepsilon_{33}^T \) | = Piezoelectric permittivity at constant stress [(coulomb/volt)/m = Farad/m] |

| \( Q_M \) | = Mechanical Q [no units] |

Note that this equation itself doesn't impose any limits on the parameters, particularly the electric field strength \( E \). Practically, \( E \) must be limited in order to prevent damage to the piezoceramic (depending on the type of piezoceramic), to prevent unnecessary increase in loss, and to prevent arcing across the piezoceramic's faces or to other surfaces.

To obtain the actual power \( P \) that can be delivered, equation \eqref{eq:10026a} must be multiplied through by the piezoceramic volume \( \widetilde{V} \) [m3].

\begin{align} \label{eq:10027a} P &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, {E_3}^2 \, \tilde{V} \, \kappa^2 \, \varepsilon_{33}^T \, Q_M \end{align}

Equation \eqref{eq:10027a} is equivalent to Woollett's (1) (p. 26) (figure G7 here). Wollett (p. 24) notes that his equation is a "rough estimate of transducer power capacity for pulse applications when heating and elastic failure are not controlling factors". The exact duty can't be specified because it depends on factors such as cooling, thermal conduction, etc. (Note that Wollett's equation specifies that \( E_{max} \) is specified at "peak a.c.". Therefore, Wollett's equation has a ½ factor that converts \( E_{max}^2 \) to RMS.)

|

|

|

Thus, equations \eqref{eq:10026a} and \eqref{eq:10027a} indicate that the acoustic power varies with the square of the electromechanical coupling factor.

Berlincourt's equation is based on two assumptions —

- Assumption — The transducer can be represented as a lumped-parameter system (e.g., per Berlincourt's heavily mass-loaded transducer with centered ceramics). In fact, practical transducers do not conform to this ideal since significant strain extends into the end masses. In that case \( \kappa \) should be replaced by \( \kappa_{eff} \). (See Woollett (1), p. 24 — "However, the transducer coupling coefficient is usually less than the coupling coefficient of the material used in its construction, and it is designated as the effective \( k \) to distainguish it from \( k \) the of the [piezoelectric] material.")

- Assumption — The transducer's response to the controlling parameters is linear (e.g., with the electric field strength \( E \)). However, this assumption would likely be violated at high drive levels (Woollett (1), p. 24). For example, see the following figure from Berlincourt (2). The assumption of linearity will be further disrupted when the ceramics are operated at an elevated temperature, typically due to internal heat generation.

Figure G8. Effect of electric field strength on piezoceramic permittivity

Thus, Woollett (1) (p. 24) notes that the predicted power will be "quite approximate" for practical transducers. However, since degrading factors (e.g., thermal) have been ignored, the power predicted by the above equations should probably be assumed as an upper limit.

Use for quality control

The effective electromechanical coupling coefficient can be used for partial qualification of individual ceramics — any piezoceramic that falls outside an acceptable range is rejected. (\( \kappa_{eff} \) should normally be supplied by the piezoceramic's manufacturer. Note, however, that the manufacturer may simply designate this as electromechanical coupling coefficient or \( \kappa \), omitting the "effective".)

Similarly, \( \kappa_{eff} \) can be used to qualify an entire transducer. If a transducer has a \( f_{oc} \) that is unusually close to \( f_{sc} \) so that \( \kappa_{eff} \) is unusually small (equation \eqref{eq:10024a}), then this likely indicates a defective transducer. (In this case \( \kappa_{eff} \) of the selected transducer is compared to an average \( \kappa_{eff} \) for known "good" transducers of nominally identical design.)

Improper use

Although \( \kappa \) is important, it is sometimes misinterpreted.

Comparing transducer designs

Different transducer designs can't be compared on the basis of their \( \kappa_{eff} \).

Consider the situation where the transducer is modified so that it has more stored energy (e.g., by increasing the density of the front or back drivers, or by machining gain into the front driver). Then the difference between \( f_{oc} \) and \( f_{sc} \) will decrease (which will reduce \( \kappa_{eff} \)) even though the power handling will not be affected.

Thus, \( \kappa_{eff} \) must be carefully interpreted. As Waanders (p. 82) notes, "Depending on the [transducer's] construction different values of \( \kappa_{eff} \) will be found. The translation to the absolute quality level is often very complicated or impossible."

Also note that \( \kappa_{eff} \) does not account for any transducer loss. Hence, two transducers could have identical \( \kappa_{eff} \) yet have vastly different loss.

Given the above considerations, \( \kappa_{eff} \) may be only marginally beneficial in comparing transducers of different designs.

Judging transducer losses

Since the parallel and series resonant frequencies are essentially independent of the transducer's mechanical and electrical losses (assuming that these are within reason), \( \kappa_{eff} \) can't be used as a criterion for judging a transducer's loss. For example, for a Branson 20 kHz 502/932R transducer (figure G5) with ceramics of either moderate quality or high quality (Prokic (1), pp. 22, 23), the following table shows that \( \kappa_{eff} \) is essentially the same for both.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Note — insofar as loss is concerned, a higher quality transducer of identical design will be characterized by —

- Lower resistance at series resonance

- Higher resistance at parallel resonance

- Higher \( Q \)

Determining κeff

\( \kappa_{eff} \) can be determined from equation \eqref{eq:10024a} if \( f_{sc} \) and \( f_{oc} \) can be determined. This is easy and accurate for a physical transducer. The result will only be approximate otherwise. Even with FEA that can simulate the electromechanical properties of the ceramics, these properties can only be approximately estimated. For example, the Young's moduli depend on the static preload. This relationship may not be known precisely even when the prestress is uniform across the piezoceramic area; this is further complicated because in many cases this prestress is not uniform. Other properties present similar difficullties.

Power output — further considerations

For this discussion, equation \eqref{eq:10027a} is repeated here for convenience —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10028a} P &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, {E_3}^2 \, \tilde{V} \, \kappa^2 \, \varepsilon_{33}^T \, Q_M \end{align}

In equation \eqref{eq:10028a}, \( \tilde{V} \) is the total piezoceramic volume. If there are \( n \) piezoceramics then equation \eqref{eq:10028a} can be written as —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10029a} P &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, {E_3}^2 \, \left( n \, \tilde{V_o} \right) \, \kappa^2 \, \varepsilon_{33}^T \, Q_M \end{align}

where \( \tilde{V_o} \) is the volume of each individual piezoceramic. \( E_3 \) is now the electric field strength across each piezoceramic.

In equation \eqref{eq:10029a}, the piezoelectric \( \tilde{V_o} \) can be replaced by the product of the piezoceramic area \( \tilde{A} \) and the individual piezoceramic thickness \( h \).

\begin{align} \label{eq:10030a} P &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, {E_3}^2 \, \left( n \, \tilde{A} \, h \right) \, \kappa^2 \, \varepsilon_{33}^T \, Q_M \end{align}

Dividing the quantity within () by \( h \) and collecting terms gives —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10031a} P &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, {E_3}^2 \, n \, \left( \frac{\tilde{A} \, \varepsilon_{33}^T } {h} \right) \, h^2 \kappa^2 \, Q_M \end{align}

The quantity within () is just the capacitance \( C_o^T \) across the thickness of an individual piezoceramic. (Since the dielectric \( \varepsilon_{33} \) is specified in the constant stress condition \( ^T \), the piezoceramic capacitance \( C_o \)must be evaluated in the same condition; hence, the \( ^T \) superscript.) Multiplying \( C_o^T \) by \( n \) would give the total transducer capacitance.

\begin{align} \label{eq:10032a} P &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, \left( {E_3 \, h} \right)^2 \, n \, C_o^T \, \kappa^2 \, Q_M \end{align}

(\( E_3 \, h \)) is the applied voltage \( V \) across each piezoceramic. The resulting power \( P \) is —

\begin{align} \label{eq:10033a} P &= 2 \pi f_{sc} \, V^2 \, n \, C_o^T \, \kappa^2 \, Q_M \end{align}